Stanley B. Greenberg is chairman and CEO, and Robert O. Boorstin is vice president, Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research.

Full article here:

https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/article-public-perspective-2001.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1adWhWtoU0wPkLnAjgE4cKTRsS2dIQr0NPR0a8CtORIZlV5A88CA065ks

A little more than a half-century ago, 63 countries established the modern Geneva Conventions to strengthen the protections afforded to combatants and civilians in times of armed conflict. In the midst of global war—one in which systematic extermination, indiscriminate bombing and mass deprivation led to millions of civilian deaths—these nations knew all too well that such rules were needed as never before.

As we enter a new century,

that need is more urgent than ever and is brought

into stark relief virtually every day. Around the

world conventional wars, involving

clashes between regular armed forces of

opposing nations, take a

terrible toll. At the same time, wars between those who

share a country or a region have

become a catastrophic way of

life. These wars are less

a collision of armies than a struggle to assert control

over areas or popula- tions. Divided

by religion, ethnicity,

traditions or territorial claims, com-

batantscompete to hold onto power or

to fill thevacuum left by the collapse of state

authority. As these conflicts stretch

on—sometimes for decades— cultural norms dissolve, chaos prevails, and civilians find themselves unable to escape the

cycle of violence.

To give voice to the victims of modern warfare and mark the fiftieth anniver- sary of the Geneva Conventions, in 1999 the International Committee of the Red Cross undertook a groundbreaking research project called “People on War.” The program, com- missioned by the ICRC and conducted

Civilians in the line of fire

by Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research (GQR) of Washington, DC, set out to survey civilian populations and combatants in 12 countries that have endured modern forms of war. The purpose was to explore people’s understanding and attitudes about the rules and limits of what is permissible in war.

Over the course of more than one year, researchers collected a massive amount of quantitative and qualitative data. National opinion surveys, focus group discus- sions and face-to-face, in-depth interviews were held in each of the war- torn countries, which included Afghanistan, Bosnia- Herzegovina, South Africa and Cambodia (see page 38 for the complete list). In all, researchers surveyed 12,860 people, assembled 105 focus groups, and conducted 324 in-depth interviews. The project also surveyed 4,525 people living in nations that are members of the United Nations Security Council, as well as Switzerland, in an attempt to understand the difference in attitudes between those living in conflict situations and those in coun- tries that play a major role in the formulation or oversight of international humanitarian issues. [The survey covered citizens of four of five permanent members of the UN Security Council. The ICRC was unable to field a survey in the People’s Republic of China.

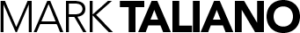

The research reveals, in essence, that modern wars have become conflicts without limits. Civilians have—both intentionally and by accident—been moved to center stage in the theater of war, which was once fought primarily on battlefields. This fundamental shift in the character of war is illustrated by a stark statistic: in World War I, nine soldiers were killed for every civilian life lost. In today’s wars, it is estimated that ten civilians die for every soldier or fighter killed in battle.

In too many nations and for too many generations, death, destruction and displacement have become the stuff of everyday life. The distinction between combatant and noncombatant has become blurred as entire societies have descended into war. Ethnic cleansing, wholesale displacement of populations, conscious acts of terror and slaughter of one’s neighbors — each has taken its place in the modern arsenal of war.

Yet the more these conflicts have degenerated into wars on civilians, the more people have reacted by reaffirming the norms, traditions, conventions and rules that seek to create a barrier between those who carry arms into battle and the civilian population. In the face of unending violence, these populations have not abandoned their principles nor forsaken their traditions. Large majorities in every war-torn country reject attacks on civilians in general and a wide range of actions that by design or default could harm the innocent. The experience has heightened consciousness of what is right and wrong in war. People in battle zones across the globe are looking to forces in civil society, their own state institutions, and inter- national organizations to assert them- selves and impose limits that will protect civilians.

Awareness of, and belief in, the power of the Geneva Conventions—the primary guide that sets limits on wartime behavior—are uneven but offer hope for the future. In the industrialized countries surveyed, the Conventions are well-recognized but generally dismissed as ineffective. In the war-torn countries, there is evidence that the Conventions can, at a minimum, help set a behavioral framework to con- strain those who take up arms. In an era when the suffering of civilians caused by armed conflict has hardly subsided, the Conventions’ principles have proven resilient in the face of constant assault.

In many of the conflicts studied in the “People on War” project, whole societies were at war. People at all levels were totally engaged in and some- times fully mobilized for battle, or they could not escape its deadly reach.

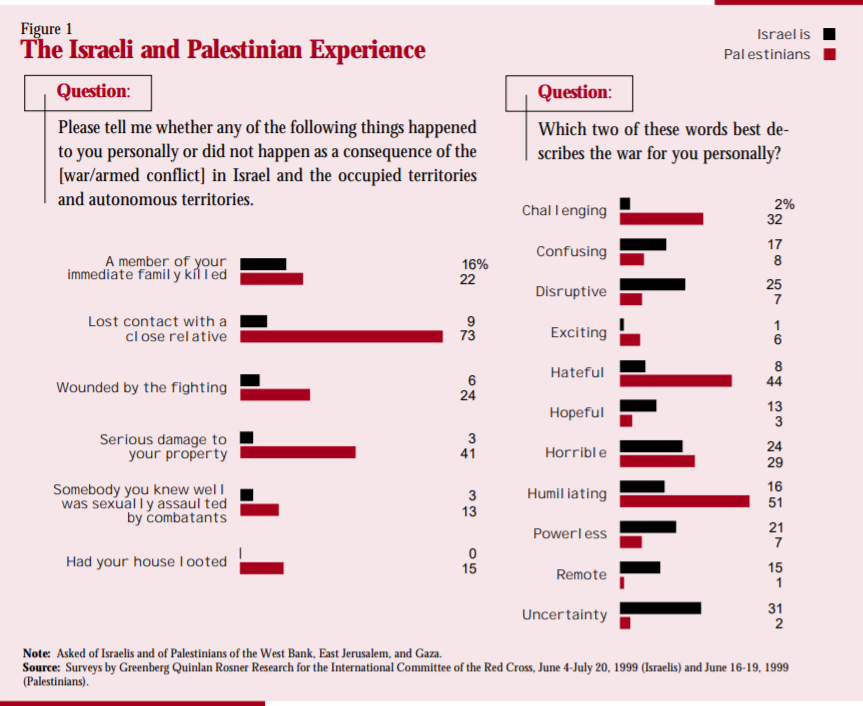

As a consequence of this total engagement, death, destruction and dislocation became the norm. Death struck the families of almost one in three of the respondents surveyed in the war- torn nations. Overall, 31% reported that somebody in their immediate family had died in the war. The death toll reached about a third of the families in Lebanon (30%), El Salvador (33%), and Nigeria (35%) and of those of the Bosnians and Serbs in Bosnia- Herzegovina (31%). In Afghanistan, more than half (53%) lost a close family member; in Somalia it was almost two-thirds (65%), and in Cambodia, an overwhelming 79%.

In the war settings surveyed, fully one-third of the population (34%) was forced to leave home. Among the Muslims in Lebanon and the Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina the dislocation was massive, affecting about half the population. In Somalia, almost two-thirds (63%) were displaced, as were four of five people in Afghanistan (83%).

The most widespread experience of civilians in these conflicts was the radical disruption of family life. More than 40% in these settings said they had lost contact with a close relative. In half the war settings surveyed, more than half had lost touch with family members, the highest levels being in Cambodia, Somalia, Georgia and Abkhazia, and among Palestinians.

The focus groups and interviews revealed the horrible brutality that accompanied these conflicts. Civilians often found themselves directly in the line of fire, facing vicious assault by combatants, opponents or even neighbors:

They raped women in front of their husbands. Once they raped [an] 11- year-old girl and threw her from the second floor. They tortured and killed children, women and old people (Georgia and Abkhazia).

Many girls were captured by the Nigerian Army, including married women. At times they raped the women in front of their husbands. If you talked they would shoot you (Nigeria).

The hardest part of the war was seeing the massacres of children and the elderly. I witnessed a massacre during this war when they killed 60 children under the age of five. Sixty children (El Salvador).

Most people in the war-torn countries believe that non- combatants should be ex-empt from the violence, and many struggle to stay out of the line of fire and avoid supporting or joining a side. But civilians, no matter how detached from the war, often find themselves recruited, pushed and compelled to join the combatants.

The total engagement of societies in war is gauged by the proportions of the population who support a side in the conflict or live in an area of conflict, or both. Among Israelis and Palestinians and in Bosnia-Herzegovina, more than two-thirds of respondents supported a side in the conflict. In some settings, support for a side was less frequent—in Somalia it was 53% and in Afghanistan 37%—but the majority lived in the war zone: 63% in Somalia and 79% in Afghanistan. In Cambodia, only 21% supported aside, but almost two-thirds (64%) lived in the area of conflict.

Combatants often cajole civilians into joining the conflict, or force them to join. In the Philippines, for example, there was a continuous effort to win over and recruit civilians with promises that families would be taken care of if the men joined the conflict. And in El Salvador, civilians were compelled to provide food for the fighters.

Residents of areas where mobilization is on a smaller scale tend to draw a more distinct line between combatants and civilians. In areas where virtually total mobilization occurs, the line between civilians and combatants is blurred and, as a result, attacks on civilians are more accepted.

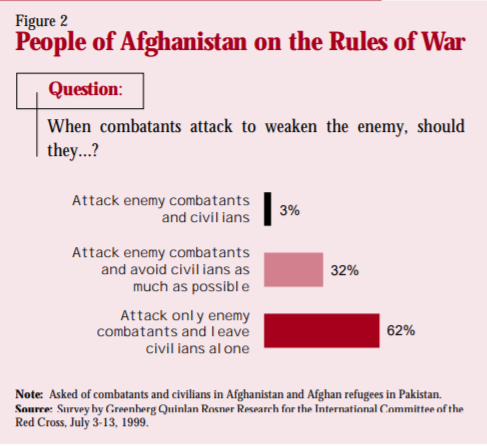

Yet overwhelming majorities of people in the war-torn countries reject practices of war that endanger civilians; their norms are based on a belief in human dignity, religion, traditions, or a personal code. Across the surveys, more than three- quarters (76%) volunteered their opinions as to what actions should not be permitted. One in five (20%) said they did not know whether there is anything combatants are not allowed to do; just 4% said everything is allowed. And almost two-thirds (64%) said that combatants, when attempting to weaken the enemy, must attack only other combatants and leave civilians alone. About one-third took a more hard-nosed view, saying combatants should avoid civilians as much as possible.

These views were echoed when respondents were asked about a series of sce- narios in which attacks on villages or towns could harm civilians. Two out of three said combatants should not put pressure on the enemy by denying civilian populations food, water or medicine; two out of three rejected attacks occurring in population centers where many civilians would die; and three out of four maintained that civilians who are voluntarily providing food and shelter to enemy combatants should not be attacked.

Nonetheless, in nearly all the surveys, sizeable minorities accepted attacks on combatants in populated areas, even knowing that many women and children would die, or sanctioned actions to weaken the enemy that would deprive civilian populations of food, water and medicine. Hostage-taking, sieges, the use of anti-personnel landmines and indiscriminate bombing all were given a place in an emerging late-twentieth century war culture in which grave threats to non-combat- ants became routine.

Combatants, not surprisingly, are more ready to put civilians at risk. Large majorities of Israelis and Palestinians said it is “part of war” (and not “wrong”) to take hostages in order to get something in exchange, to attack civilians who collaborate with the enemy, or to keep mortal remains to get something in exchange. More than 40% of Israelis and one-third of Palestinians accepted attacks on populated areas, knowing that many women and children would be killed. And almost two-thirds of Israelis (66%) and nearly half of Palestinians (46%) said it is acceptable to plant landmines to stop the movement of the enemy even though civilians might step on them accidentally. [This contrasts wildly with the opinions of those in areas of more limited conflict. About nine in ten respondents in Colombia, El Salvador, the Philippines and South Africa were opposed to landmines.]

I n spite of widespread beliefs that war should have limits, the limits are routinely ignored. When asked why they think combatants harm civilians despite prohibitions against such behavior, people focused on the sides’ determination to win at any cost (30%), the hatred the sides felt for each other (26%), and their disregard for laws and rules (27%). These views were reinforced by a sense that others were doing the same thing, thus demanding reciprocity (14%).

Some believed that most people are following the orders of leaders who have larger designs (24%). This interpretation was dominant in El Salvador, where 59% thought combatants had been told to breach the limits. It was also a strong interpretation among white South Africans.

Others thought that people in a conflict environment had just gone out of control: soldiers and fighters had lost all sense (18%) or were under the influence of drugs or alcohol (15%). In Georgia and Abkhazia, people believed these were significant factors in what happened to civilians in that conflict, though, in the latter case, they also focused on hatred.

The results of the survey and the qualitative research point to a combination of factors that, taken together, have proven lethal. With whole societies involved, civilians and soldiers are becoming conceptually indistinguishable. The more conflicts engage and mobilize the population—and the longer they last—the more hatred grows and people take sides. Revenge, the cycle of violence and the perceived righteousness of one’s cause only add fuel to the fire.

Across the board, the majority of respondents in the four UN Security Council nations surveyed believe in absolute protection for civilians during wartime. Sixty- eight percent said that combatants should “attack only enemy combatants and leave civilians alone.” Sixty- four percent of those in war-torn settings agreed.

A significant minority of people in both groups of countries, however, agreed with another, conditional response: they said combatants should “avoid civilians as much as possible.” About one-quarter (26%) of the respondents in the Security Council nations chose this response, compared with nearly one-third (29%) of those in war-torn countries.

Among the Security Council countries surveyed, respondents in the United States demonstrated the greatest tolerance of attacks on civilians. A bare majority (52%) said combatants should leave civilians alone, while 42% said civilians should be avoided as much as possible. In contrast, nearly three-quarters of respondents in the other three Security Council countries adopted the absolute standard, while 20%—half as many as in the American survey—chose the conditional option. Across a wide range of questions, in fact, American attitudes towards attacks on civilians were much more lax.

The Geneva Conventions are not widely known, yet some evidence suggests they can help provide a framework for more constraints on behavior during wartime. Thirty-nine percent of the people in the armed conflict settings surveyed had heard of the Conventions. Awareness was uneven, and specific knowledge of their function was uncertain. However, according to the assessments of the interviewers— most of whom worked for national Red Cross or Red Crescent societies—about 60% of those who said they had heard of the Geneva Conventions offered a roughly accurate description of their content. This means that about one in four across all the settings surveyed has an accurate knowledge of the Conventions.

In conflicts that have been internationalized to a great degree—such as Bosnia- Herzegovina and the Israeli-Palestinian

set boundaries. The data also indicate that people unaware of the Conventions are more likely not to help or save a defenseless enemy combatant who has killed someone close to them, and are more likely to deny minimal rights to captured combatants.

When people were given information about the Geneva Conventions, a sizeable majority in the conflict settings concluded that the Conventions can make a difference. People were read the following description: “The Geneva Conventions are a series of international treaties that impose limits on war by describing some of the rules of war. Most countries in the world have signed these treaties.”

After hearing the statement, 56% of all the respondents concluded the Geneva Conventions can “prevent wars from g e t t i n g worse,” com

in the four Security Council countries were almost equally divided between respondents who said the Conventions can help prevent wars from getting worse (43%) and those who said they “make no real difference” (47%). Respondents in the United Kingdom and the United States were far more skeptical than their counterparts in France and the Russian Federation. More than one-half of American and British respondents (57% and 55%, respectively) said the Geneva Conventions make no real difference, compared with 45% in France and only 33% in the Russian Federation.

Nonetheless, the generally optimistic stance on the part of respondents in war-torn countries provides encouraging evidence that education about the Geneva Conventions could make a difference in the behavior of combatants

conflict—awareness was more wide- spread: 80% in Bosnia-Herzegovina were familiar with the Geneva Conven- tions, as well as 89% among Israelis and 65% among Palestinians.

In many places, only about a third of respondents had

heard of the Geneva

pared with 28% who thought they “make no real difference.”

Despite the mas- sive upheavals people had en-

People of Afghanistan on the Rules of War

Conventions—Colombia (37%) and El Salvador (33%), for example. In other

settings—Cambodia, Afghani- stan, Georgia and Abkhazia—one in five said they were aware of the Geneva

Conventions. In contrast, two-thirds of

respondents (66%) in the Security Council

countries surveyed had heard

dured, in eight of the twelve coun-

tries surveyed a significant major-

ity was relatively positive about the efficacy of interna- tional conventions

and civi l ians 3%

Att ack enemy comba t an t s and avoid civi l ians as much as possib l e

Att ack on l y enemy comba t an t s and l eave

civi

l ians a l one

32%

62%

of the Geneva

Conventions, while about one-third (31%) had not.

in shaping the course of war.

Note: Asked of combatants and civilians in Afghanistan and Afghan refugees in Pakistan.

Source: Survey by Greenberg Quinlan

Rosner Research for the International Committee of the Red Cross, July 3-13,

1999.

Consciousness of the Geneva Conventions is important. At a minimum, it helps set out a behavioral framework for those who take up arms. When faced with morally difficult decisions—concerning civilians, combatants and prisoners—a basic understanding of a legal frame- work can at least help combatants to set boundaries. The data also indicate that people unaware of the Conventions are more likely not to help or save a defenseless enemy combatant who has killed someone close to them, and are more likely to deny minimal rights to captured combatants.

higher level of awareness of the Geneva Conventions in countries that had not recently experienced war on their soil did not, however, lead to a higher degree of belief in their efficacy.

After being read the

description of the Geneva Conventions, those surveyed

in the future. Today the 188 signatories of the Geneva Conventions have an historic opportunity to rewrite the rules and do everything within their power to shield civilians from the wars that envelop them. The “People on War” project provides important evidence that those who bear the scars of war would benefit from such protections.

![Virginia Sen.Richard Black [ Retired]: Syrian election victory is almost like a war victory celebration/ Syria Times](https://marktaliano.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Senator-Black-100x70.png)